Yesterday a journalist asked me during an interview whether, given that we’re talking about diversity and that each person is different, it wouldn’t be better to abolish concepts such as disability or autism, because they are negative identifications for the person who is labeled by them.

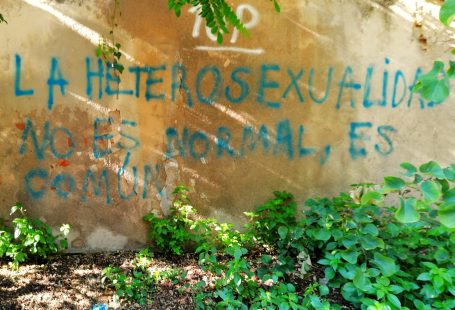

Of course, at first glance we might think that these are just labels, and that obviously they must be transcended. And maybe this is true if we’re talking about a certain type of meaning attributed to them, one of deficient functioning, of an inferior, incapable, unusable person. But those labels are fundamental because they allow the creation of group identity, the kind of cultural belonging that is fundamental for each individual, and that people who belong to the culturally dominant group, the majority, can serenely take for granted.

Therefore, when we are talking about autism and autistic people (but also about disabilities and other minorities), the use of a label makes sense from a political and social point of view, because it allows for the creation of a minority identity, which is not necessarily harmful, and is in fact fundamental for someone to achieve social, political, and ultimately also individual visibility as a person with certain characteristics.

The problem is that for decades, precisely as has happened for disabled people (or people with disabilities, as many prefer to be called), we Autistics have been studied, cataloged, observed and judged from one of two perspectives that clearly show prejudice: either as defective beings who are in need of care or interventions to become as “normal” as possible according to a medical rehabilitation model, or based on our productive capacity, on our work performance, following an economic model.

The problem with both of these approaches is that they don’t consider the point of view of the people they study and catalog, and for whom society makes legislative, political, medical and economic decisions that have extremely practical repercussions on their lives. The so-called social model instead proposes the idea that a person does not live in a vacuum, but rather that their existence is the result of interaction with society, and if this society “disables” the person by placing a series of obstacles and barriers before them, then society becomes part of the problem and should therefore be part of the solution.

The creation of a group identity is important for the vindication of basic rights and opportunities which, without the cultural contribution of a socially identifiable group, will continue to be granted in a series of paternalistic acts, tossed from above, donated with condescension to those who then continue to be seen as inferior, broken, unnecessary from a productivity or economic point of view.

The prevalence of the medical and economic gaze in the collective narrative of autism is what prevents the voice of Autistic people from acquiring equal dignity to that of others, for example specialists, precisely because if we are defective, abnormal, negatively non-compliant creatures, then we don’t have the capacity to know what is best for us, and obviously we aren’t considered capable of directing the social and economic policies that should contribute to breaking down barriers.

Let’s be clear, I don’t like the idea of belonging to a “minority” either, and I support those who argue that labels should be abolished, and that minorities would not exist if we could understand that everyone is different. The problem is that, before we can eliminate minorities, we must abolish the most problematic label, the most powerful and intransigent minority, the one that defines itself as the majority and that currently dictates political, economic and social rules and shapes the society in which we live, keeping all kinds of barriers in place. And that falsely self-defined majority will continue to do so unless minorities are able to make their voice, their version of history, their culture heard.

Another fundamental aspect concerns research [1]. If we continue to follow the medical rehabilitation or economic model, in short, if we Autistics are seen as inferior, defective, economically useless, even the objectives of scientific research will continue to be dictated by the gaze of the majority. Studies and experiments will therefore aim to confirm deficits, to look for the causes of defects, to ask how to cure or prevent what, from this point of view, continues to be seen as a pathology to be eradicated.

The influence of Autistic people must become fundamental in determining research objectives. We cannot be part of the research only as an object of study, but must also participate in the design of the experiments, and decide which directions research should take in conjunction with others involved in the project. A striking example of the necessity of this change concerns Theory of Mind and Autistic empathy.

When Simon Baron-Cohen decided to study the Theory of the Autistic Mind (the ability to attribute mental states and feelings to oneself and to others) he did so from a perspective of deficiency. His purpose was to understand where mental deficit resides, how we Autistics are deficient in that area. And he gave birth to the idea that autistic people don’t have empathy.

But it was a wrong point of view that created a false theory, which added yet another stigma to an already heavily stigmatized identity; the study involved a biased starting point, distorted objectives, and a methodology [2] calibrated on misunderstood functioning, which resulted in us being considered deficient even in empathy. And this error continues to be boosted by a narrative enamored with the idea that non-conformity with the majority must necessarily be defective, inferior, deficient.

Only when the question was posed without the prejudice of a deficiency-driven and pathologizing gaze, only when Damian Milton, an Autistic researcher, studied Autistic empathy, did a sensible theory arise that sees reciprocity (a word that should be used more often) as the problem: it’s not we Autistic people who lack empathy, it’s a mutual problem. We have difficulty understanding neurotypical people, and they have difficulty understanding us neurodivergents, it’s a matter of different codes and interpretations. This change of perspective is ultimately trivial but was unattainable without the direct contribution of the minority that was being studied.

The formation of an Autistic culture, of a group with an identity provided by a different world view, is therefore essential to help society understand the needs, aspirations and desires of that group. Cultural belonging is also important in the formation of a personal identity that does not pass through the distorting lens that creates insecurity, a sense of inferiority, and uselessness in many autistic people. Because without a reference culture we grow up thinking that we aren’t enough, we believe that something is always missing in order for us to be like everyone else; we live with the conviction of constantly having to do more, because our way of being is wrong.

NOTES

[1] Hahn, H. (1993). The Political Implications of Disability Definitions and Data. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 4(2), 41–52.

[2] Gernsbacher, M. A., & Yergeau, M. (2019). Empirical Failures of the Claim That Autistic People Lack a Theory of Mind. Archives of scientific psychology, 7(1), 102–118. doi:10.1037/arc0000067

[3] Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the “double empathy problem.” Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. doi:10.1080/09687599.2012.710008