(Kindly translated by Andrew Dell’Antonio)

On March 20, the President of the Spanish Council of Ministers, Pedro Sanchez, updated Royal Decree 463/2020 which establishes the state of emergency and mandatory isolation due to coronavirus, allowing some categories of people to leave their home while remaining in compliance with the safety rules against contagion.

What a civilized gesture, I thought, reading the official update of the decree. I confess that I felt lighter at the idea of being able to go for a short walk in times of overload, when the alternative is the explosion of a meltdown or the closure in a shutdown from which I would emerge devastated after days of total block.

Also because, if for some this imprisonment is becoming unsustainable due to boredom, for those like me who were immediately converted into “smart workers” our workload has tripled and work hours have become increasingly flexible until they disappear, making the full day a long working session interspersed with short breaks.

This means that I don’t have the luxury to be reduced to an unusable vegetable for two or three days due to cognitive overload or to explode in a destructive crisis, which will then leave me out of pocket for a while, as a consequence of sensory overload.

Being also hyperactive and extremely anxious, the only effective way for me to quickly release tension has always been physical activity; even just a quick half-hour walk, but I need to be able to go out, breathe fresh air, stay in open spaces and move, unload, get tired physically. When I had the harpsichord building workshop, it was so physically tiring that I was able to unload a lot of accumulated tension while working, but now with my university work, stuck at home in front of a screen, everything is different.

Yet for more than a week I still haven’t left my apartment because I’m afraid. I am terrified of the neighborhood lookouts posted on the balconies, informers who spend their days spying on the movements of others, screaming insults and clamoring for the arrival of the police to arrest the violators, often even throwing eggs at the alleged criminals.

Leaving the apartment hoping to reset my overloaded nervous system, but instead ending up adding more anxiety to what is already present and getting even closer to explosion, is too risky. I already imagine the scene: walking through the deserted streets, I look around me terrified and then, suddenly, from a balcony someone starts shouting at me.

What would happen to me but also to many other Autistic people in a similar situation? Probably, the first reaction would be to respond to the insults, to explain that I am in compliance, that I can go out because I am Autistic. And here I foresee two scenarios, unfortunately both end badly.

In both hypotheses, the premise is the same: the informers would not believe me, and would continue to scream attracting the attention of the neighbors who would happily and enthusiastically join the public verbal stoning (which, as I said, here sometimes leads to the launch of eggs). Mind you, it is not an exaggeration, there are reports in the newspapers of mothers or fathers who came out with their Autistic children and ended up in the idiotic meat grinder of the balcony vigilantes [1].

A parenthesis is now necessary to reiterate a concept on which I often insist and which at times, superficially, has been considered an unnecessary habit: when I say that language is fundamental because it creates reality, and that if we choose words carefully we can contribute to a change both positively and negatively in the world in which we live, I refer to this. In our case, an incorrect use of language has led to the creation of a doubly false reality.

In the first place false because the continuous references to war [in Spanish response to the Coronavirus], the semiotic of war that I wrote about in an article a few days ago [2], has created a dangerous state of alert, a situation in which ordinary citizens feel obliged and, even worse, entitled to spy on other individuals whose background they do not know, staging summary trials that end with the exposure to public pillory of the alleged criminals.

We are now in a situation where the idea of ”war” or “battle” against an invisible enemy, spread by short-sighted rhetoric, has suspended the rule of law even on the balconies. The emergency wants no exceptions and so go ahead, vent your frustration on your neighbor without asking questions, who cares about presumption of innocence, fair trial, those civil rights that are so precious but so fragile. Those foolish spies don’t realize how much their behavior, eroding civil and peaceful coexistence, has contributed to creating a state of tension and summary justice that at the first opportunity will turn against them like a boomerang.

The second distortion of reality, that a superficial use of language has helped to create and maintain, concerns the image of the Autistic individual. In several articles I have written about how risky it is to use words and expressions that don’t describe the reality of autism correctly. Every time someone replied that in short, since I am picky, it’s evident that I am Autistic, too rigid, because facts matter more than words.

Now words are showing us how harmful this way of thinking (and consequently of acting) is. The words “child”, “autism”, “disabled”, together with expressions such as “non-verbal” “disease to be fought”, “special little angels”, “destroyed families” and the like, have created the stereotype of the autistic child. This incorrect language, sometimes used superficially, other times with intentionality and less noble ends, has created a fictitious reality, namely that autism is exclusively a childhood condition, that does not coincide with the truth [3].

In this alternative reality, if I left the house to walk in a moment of overload, even if I had the right by law, I would almost certainly be targeted by the balcony snipers. It would be of no use to explain that I am Autistic, because already people do not generally believe that an adult who speaks can be on the spectrum, let alone now that we are in a “war” and we must flush out the enemy at any cost.

The reality, the real one, in which Autistic children grow up and become Autistic adults, is not even taken into consideration by the majority of the population. Thanks to an improper use of language, two absolutely false concepts have been conveyed: the idea that only children can be Autistic, and that autism is a disease, an error that lets you immediately imagine the idea of ”cure”.

In the confused and uninformed collective imagination, the Autistics are therefore exclusively “children” “suffering” from a “terrible disease.” Nobody asks what happens to these children. Indeed, some have the answer: “they heal”, or “improve” (based on which criterion they improve, then, this is not known). And I guarantee you that there are many people who believe this, also because this distortion of reality operated by incorrect language is supported by the media: I have not read a single article concerning the exception to the law decree in which adult autistic people were named, least of all level 1 adult Autistics with good verbal skills, that is, those like me who at first sight do not seem Autistic, but who carry equally the hidden characteristics and difficulties of the condition.

Returning to our hypothetical walk to calm my overload, I would therefore find myself involved in a highly stressful situation that would trigger an out of control reaction, and I speak from both personal and indirect experience. I would probably start to become upset, I would try to explain that they are wrong, that I AM truly Autistic, that Autistic children grow up etc., and then, after the point of no return, the two hypotheses of which I spoke at the beginning could occur.

The first is that I would run away, probably crying in desperation, because crying is for me a phenomenal relief valve but also another reason for ridicule and social stigma. I would run away but in pitiful conditions, and then I wonder: would I be able to go home? The answer is that I don’t know, because in situations of similar crises but without the aggravation of the “state of war”, I had great difficulties and need for help.

The second hypothesis is that, invoked by the balcony executioners (once upon a time garden dwarves were used as kitsch decoration objects, today we have balcony executioners), the police arrive. Here in Spain it has happened to several parents with Autistic children, those who therefore fall under the stereotype of the “exclusively childhood disease”, and even in those cases it was difficult to make the balcony informers understand their needs, especially when the kids seemed “high-functioning”, that is, they appeared “normal” to those who have wrong information but at the same time feel the irrepressible need to flap their tongues.

In our second scenario, therefore, the arrival of the police would be a risk absolutely to be avoided. Are we sure agents would be prepared to handle such a situation? In fact, I could try to explain myself but not be believed, the insults from the balconies would increase (unfortunately, I have witnessed such scenes) and my nerves would give way dangerously. Surely I would have a certificate in my pocket stating my condition but, in the chaos of the moment, I might not think of taking it out, or remember it when it was too late, once I had exploded in a terrible meltdown.

At that point I would probably be in handcuffs, carried away amid the applause of the fascist-snipers hidden on their balconies. Do you think I’m exaggerating? Then read the articles in the notes [4], watch the video in the second link, and you will understand how the inadequate preparation of law enforcement officers who arrest Autistics — even minors — who are experiencing a meltdown is a real problem.

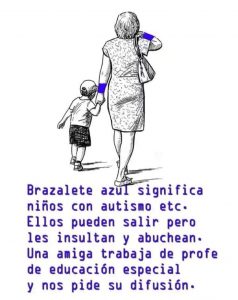

Here in Spain, as I have already written in another article, they have suggested to Autistic people, or rather to parents of Autistic “children”, since we Autistic adults do not exist in the eyes of the press, to wear something blue to indicate that — hey, my kid is autistic, he can go out, don’t insult him! Now, putting aside my aversion to the color blue being associated with autism as a symbol chosen by an association (Autism Speaks) that does not allow the self-representation of Autistics, are we really sure that the balcony informers are aware of its meaning?

Then there is a moral issue that is no less worrisome. I am not sure that a society that does not grant the benefit of the doubt, in which the dictatorship of summary judgment and the criminalization of anyone who APPARENTLY does not respect the rules has been established, is a civil society. What kind of community is one in which, to avoid being pilloried or declared a scofflaw when you are not, you must display symbols or signs by which to be recognized with the risk of being then publicly stigmatized? What happens to my freedom not to let my neighbors know I’m Autistic?

Language represents the foundations on which actions are built, nobody can deny it, and the superficial or deliberately distorted use of such an important and powerful means is inadmissible even in emergency situations, especially because once you come out from emergencies, there remains the reality created by the rhetoric of exceptionalism, a reality made of mistrust, individualism, and suspicion.

Returning to the importance of language in the description of autism, here too I would worry a little more about the message that is conveyed to society. Perhaps it is appropriate to leave more room for us Autistics, those directly concerned, and recognize the right for us to self-represent. Don’t think this is such a foregone conclusion, because if you read articles and interviews on autism, you will see that Autistic’s contributions are still paradoxically minimal and often relegated to the role of pure anecdote.

With all due respect for the accounts of autism which, although very close, do not stem from lived experience, in one’s own body, I believe it is essential to recognize the vital importance of first-person accounts of neurodiversity as the only source of first-hand knowledge. Everything else, absolutely everything, can only describe it from the observer’s point of view, as close as you like, but still an observer and not a protagonist.

The point of view of Autistic people who are able to communicate, regardless of the mode used, is the only one that can really explain what happens inside us, for what reasons we react in certain ways to particular situations, what we feel when we are forced to become what we are not, just in order to please a society that is unable to live with diversity; honoring Autistic perspectives it is the only possibility we have of creating cultural change towards neurodiversity.

Thanks to a social barbarization that I hope is only temporary, and to a narrative of autism that does not correspond to the truth, I will not leave the house, even if I am legally in the right to do so, because I know that I could encounter even greater problems than a short walk would solve for sure, and I will pay for the consequences of this impossibility to go outside on my work and on my health. Many people, however, will not be able to abstain from going out in order to avoid more extreme distress generated by forced home isolation. Among these there will also be many children accompanied by a parent, some of these children at first sight will not seem Autistic, because the image that people have of autism is limited and does not embrace all the possible manifestations of this condition.

And, regardless of how much autism is visible or not, I find repugnant the very idea of having to justify a need guaranteed by the law by wearing scarves, bracelets and blue T-shirts or any other symbol, due to the regurgitation of a dark past that seems to return with more and more arrogance.

NOTES

[1]https://www.lavanguardia.com/…/panuelo-azul-autistas-chivat…

[2] https://www.fabrizioacanfora.eu/la-semiotica-di-guerra-e-l…/

[3] STEVENSON, J. A., HARP, B. & GERNSBACHER, M. A. (2011). Infantilizing autism. Disability Studies Quarterly, 31(3).

[4] https://www.scotsman.com/…/scottish-child-autism-removed-po…

[4] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/…/Father-shares-video-autistic-…

Many thanks to Andrew Dell’Antonio for his translation into English